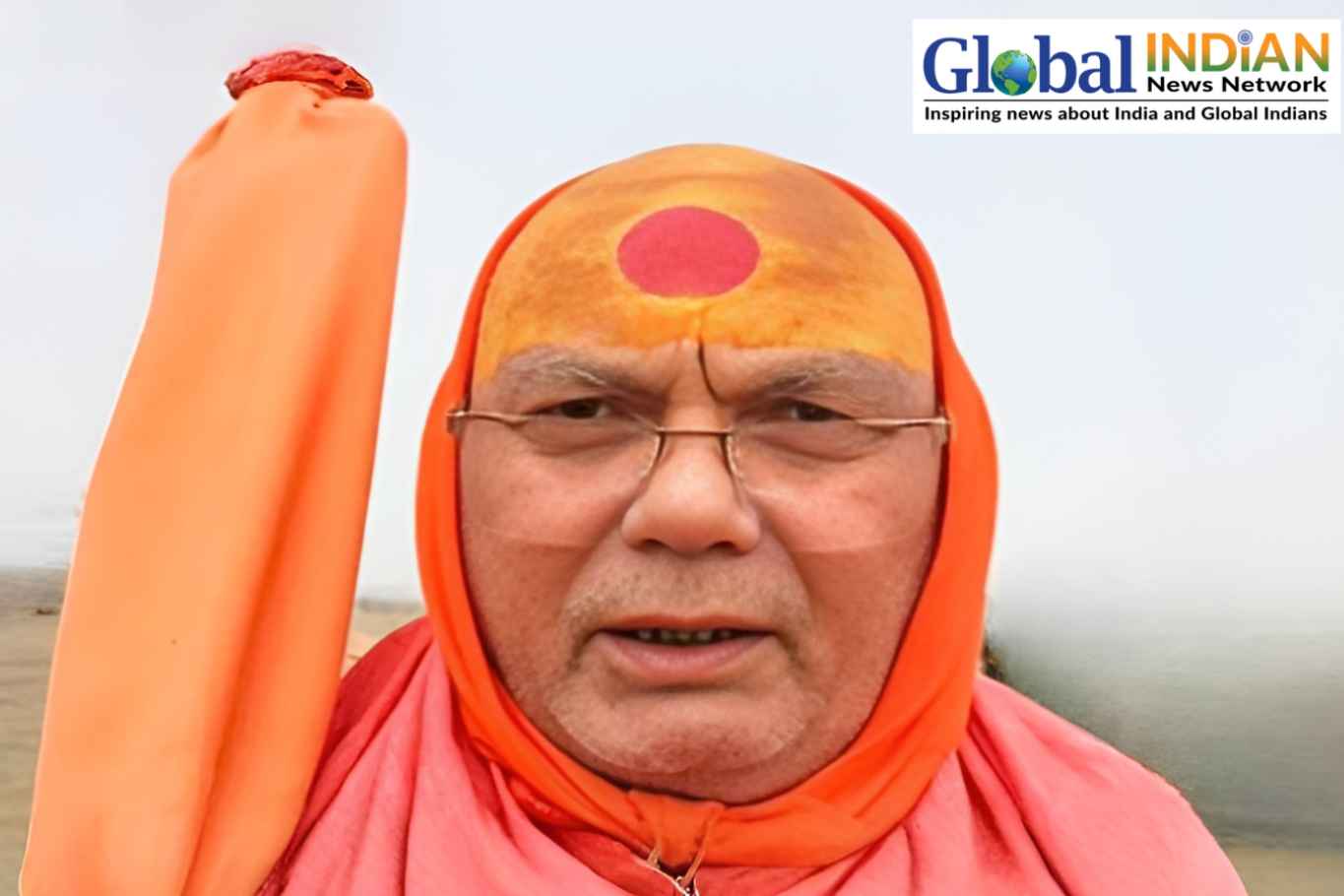

Swati Thapa, a central figure in the Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP), is careful with her words. “People want the king back,” she asserts, “not as a ruler but as a guiding force, a stabilizer. They also want Nepal recognized as a Hindu state. These aren’t just political slogans; they reflect the people’s survival instincts.”

The RPP, founded in 1990 after Nepal’s transition to multi-party democracy, started with four parliamentary seats in 1991. Despite fluctuating influence, it has often played a pivotal role in governance. In the 2022 elections, the party secured 14 out of 275 parliamentary seats. However, by February 2023, it had withdrawn from the coalition government.

The party has long advocated for three core changes—reviving the constitutional monarchy, dismantling the “costly” federal structure, and reinstating Nepal’s Hindu identity. Thapa insists that Nepal’s secular transition happened without public consensus. “Over 80% of Nepalis still prefer a Hindu state,” she claims. Addressing concerns that RPP’s stance might alienate minorities, she clarifies, “This isn’t about discrimination; it’s about preserving our identity while respecting all religions.”

Thapa further alleges that forced religious conversions, particularly in impoverished areas, are altering Nepal’s cultural fabric. She accuses foreign aid groups of pushing these changes. “We value religious freedom, but not at the cost of Nepal’s heritage,” she says.

Former King Gyanendra Shah’s recent return to Kathmandu has drawn massive crowds, though he remains silent. Whether this is a strategy or a lost opportunity is unclear. Thapa insists, “He’s above politics, and we don’t want to involve him in daily affairs. But people trust him. His silence carries weight.” She confirms that RPP is in contact with the royal family and believes monarchy should stay clear of political maneuvering.

On the question of succession, Thapa is candid. “It won’t be automatic. Gyanendra has shown no interest in ruling. It could be his son, grandson, or another family member.” She emphasizes that Nepal’s monarchy, if restored, would be symbolic, with executive powers resting in an elected prime minister.

Even if RPP’s push for monarchy succeeds, the process will take time. And if not a king, then who? “There’s no Plan B,” Thapa admits. “The republic hasn’t provided a leader the people can trust. That’s why we stand by the monarchy—not out of nostalgia, but necessity.”

This sentiment has extended beyond the party. What once was an RPP-driven movement has now turned into mass protests. On March 28, demonstrations escalated, resulting in two deaths, over 100 injuries, and more than 50 arrests, including RPP members Rabindra Mishra and Dhawal Shumsher Rana.

Thapa clarifies that while RPP supports the movement, it is not orchestrating all protests. “We morally back those who align with our vision, but this is a people-driven effort.” She insists RPP’s demonstrations have been peaceful and accuses authorities of provoking violence. “We have footage showing police in plain clothes firing tear gas from rooftops at unarmed crowds.” The party demands an impartial investigation while continuing protests across all 77 districts.

The growing unrest, Thapa believes, stems from a deep sense of frustration. “People aren’t just angry. They’re tired—of corruption, rising prices, and instability.” She sees the absence of party flags at rallies as a sign of broader support. “People carry Nepal’s flag, not RPP’s. This is bigger than us—it’s about Nepal.”

One controversial figure in these demonstrations is Durga Prasai, a former Maoist whose fiery rhetoric has drawn criticism. Thapa states, “We align with his cause, not necessarily his methods. Our commitment remains peaceful.”

As the protests continue and government suppression intensifies, Thapa remains resolute. “This isn’t a passing storm. It’s a reckoning—and it’s just getting started.”