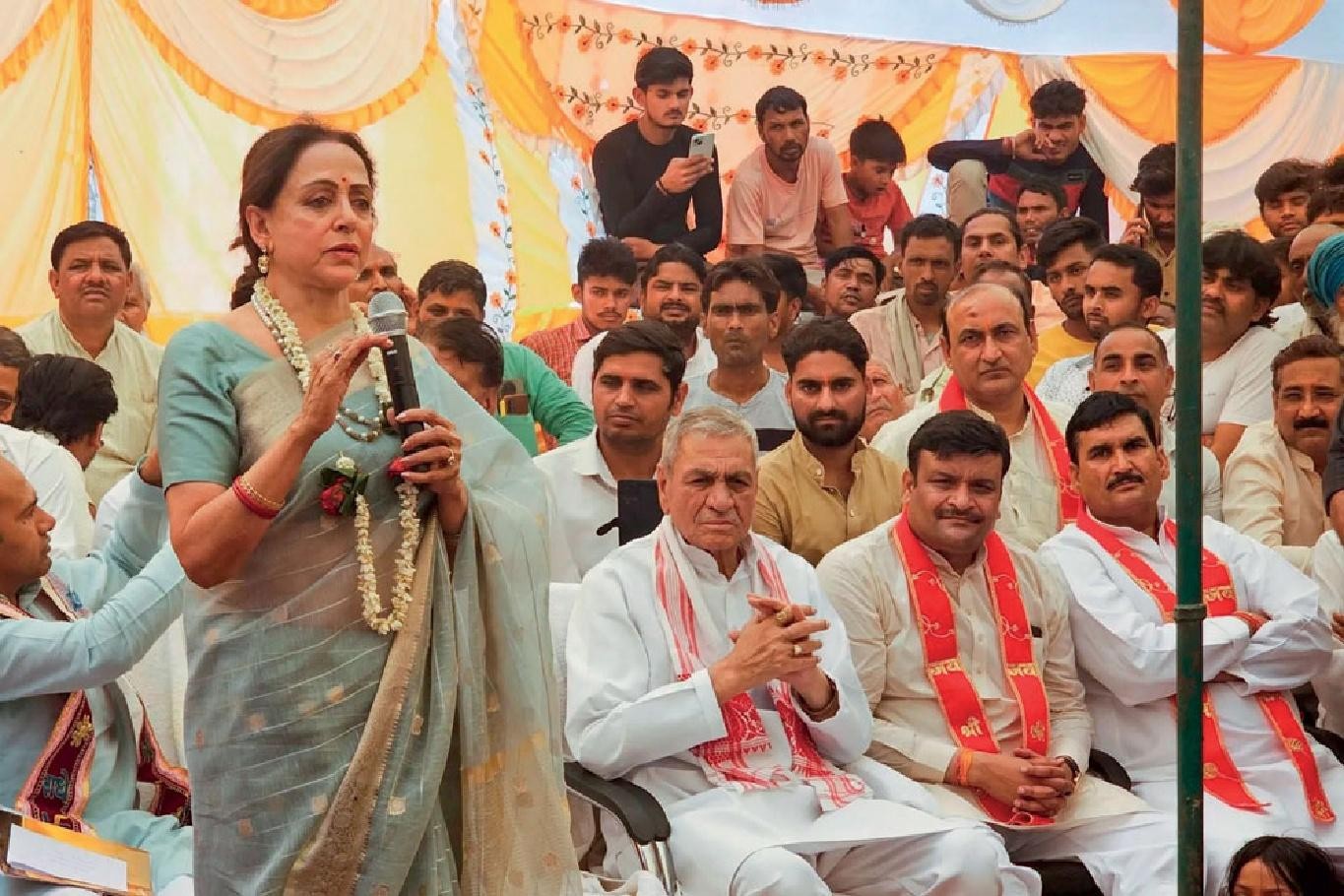

Hema Malini, a Bollywood icon, has maintained a rather elusive presence in the Mathura Lok Sabha constituency, despite winning twice consecutively. Residents of the villages and small towns on the route to the pilgrimage center of Vrindavan feel that their local MP is seldom seen except during election periods. To many, she remains a glamorous figure more visible on television than in their locality. Despite the criticisms, Malini insists that Vrindavan is her permanent home. Nonetheless, she appears poised to secure a third term in the Lok Sabha, a rare feat in an era where voters’ demands and political preferences are constantly evolving.

Mathura and Vrindavan are not immune to the rising expectations and social mobility affecting the political landscape. In rural areas like Chhata, Barsana, and Govardhan, local grievances resonate among both young and old residents. Promises such as the long-delayed sugar mill, irregular procurement of wheat, mismanagement of local temples, petty corruption, and demands for better land compensation are hot topics of discussion even a week after the April 26 vote. Open’s journey through these regions found that the elections remain a significant subject of debate, reflecting the reasons behind voters’ choices amid diverse arguments. A notable drop in voting percentage from 61% in 2019 to 49.3% this year has fueled speculation about the election outcome. The apparent voter apathy may suggest a sense of ennui, though interpreting this further might be risky.

In Chhata, early morning discussions among shopkeepers highlight the Yogi Adityanath government’s achievements in transparent recruitment and law and order. While a silent observer points out the comparison with the Samajwadi Party’s tenure, favorable mentions of Yogi’s handling of public services and law enforcement indicate a leaning towards the BJP. Despite some discontent, locals appreciate the transparency and fairness of the current government’s processes. The perception of reduced criminal activities and communal violence under Adityanath’s leadership, compared to the SP’s rule, seems to solidify BJP’s support, with many voters endorsing the “double engine” governance of BJP at both state and national levels.

In Nandgaon, young men express frustrations over a promised but non-operational sugar mill, which is seen as crucial for local economic activity. Their dissatisfaction extends to the management of the Nand Bhavan temple. Despite these grievances, they agree that the vote favored the BJP, driven by support for Prime Minister Modi rather than the candidate. The BJP’s alliance with RLD leader Jayant Chaudhary is expected to bolster support within the Jat community, a significant voter base in the Mathura Lok Sabha seat.

Yogi Adityanath’s campaign in Mathura emphasized BJP’s “India first” stance and initiatives to boost religious tourism. Places like Barsana and Nandgaon have seen increased pilgrim traffic, benefiting local commerce. Despite some dissatisfaction with land acquisition plans and compensation rates, Adityanath’s reputation for maintaining law and order seems to secure BJP’s advantage. Farmers in Barsana, while discussing compensation disputes, acknowledge Adityanath’s effective administration in reducing communal violence, reinforcing BJP’s favorable position.

Govardhan, with its rich religious heritage and pilgrimage sites, has seen growth due to its association with the life of Lord Krishna. Despite concerns about the distribution of economic benefits from religious tourism, many residents appreciate the reach of central welfare schemes and anticipate further development under Modi’s leadership. Even with some delays in administrative processes and the persistent influence of the BSP among Jatavs and Muslims, BJP remains the preferred choice for many, driven by the promise of accelerated development and Modi’s enduring appeal. The sentiment in this region, steeped in stories of Krishna’s miracles, suggests that BJP’s momentum, initiated in 2014, continues to resonate strongly.