The previous century witnessed a remarkable narrative of yoga teachers disseminating their knowledge to distant corners of the world, leading to the transformation of local religious traditions. Yoga studios can now be found in diverse locations, even in small towns across Peru, South Africa, and Hungary.

The previous century witnessed a remarkable narrative of yoga teachers disseminating their knowledge to distant corners of the world, leading to the transformation of local religious traditions. Yoga studios can now be found in diverse locations, even in small towns across Peru, South Africa, and Hungary.

This historical movement mirrors a phenomenon that occurred over 2,000 years ago in the Himalayan region, spanning both east and west. While the popular history focuses on yoga and tantra spreading to China, Japan, Tibet, and Southeast Asia through Buddhism, only specialized scholars have traced its migration to Samarkand, Bukhara, and further into the Slavic lands.

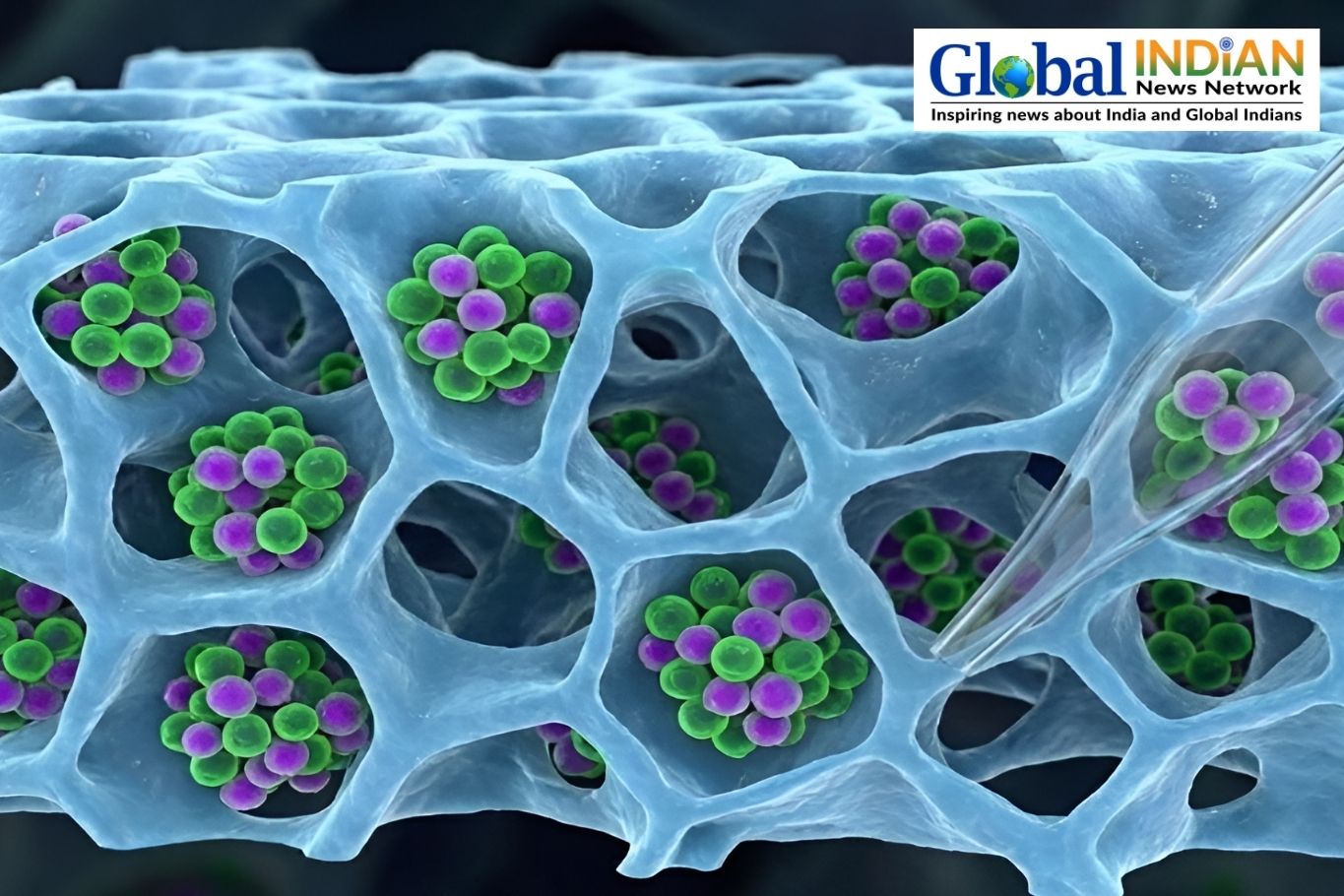

The migration of yoga to Central Asia continued for centuries, and a similar process may be unfolding today. While contemporary interest in yoga often revolves around physical well-being through āsanas (postures), yoga’s essence lies in the exploration of consciousness, which is currently at the forefront of scientific inquiry.

To those practicing yoga, the connection between āsanas and consciousness may seem unexpected. However, considering that we are both body and mind, āsanas benefit the body while practices like pranayama (breathing exercises) and meditation prepare us to recognize and ultimately gain control over the realm of the mind and awareness.

Consciousness captivates physicists and neuroscientists as they seek to understand the origins and location of awareness or the self. AI researchers, sociologists, and politicians are also intrigued by the potential of conscious machines and the profound impact they could have on technology and society.

The concept of self lies at the core of consciousness and has been central to Indian civilization since ancient times. In Hinduism, the self is referred to as the ātmā or Shiva. In the region of Kashmir in northern India, which was a renowned center for scientific and scholarly pursuits associated with Shiva, the self was conceived as “Light” (Prakāsha in Sanskrit). Yoga practices serve as a means to merge with the inner light.

If Shiva symbolizes light and represents the male principle, the body through which one strives to perceive the light belongs to the goddess Shakti, representing the female principle. Yoga, therefore, represents the union of Shiva and Shakti—light and the knowledge cultivated within the mind.

The Varied Representations of Shiva in Yoga

The artistic portrayal of Shiva often features multiple faces, although in the form of aniconic representation, there is no face at all. The concept behind the multiple faces is that Shiva, as the embodiment of consciousness (ātmā), exists in all directions. It is common to find depictions of Shiva with 1, 3, 4, and 5 faces, with the two-faced representation symbolizing both Shiva and the Goddess.

The symbolism associated with the four faces is described in the Mahabharata: the eastern face represents sovereignty, the northern face represents perfection, the western face represents prosperity, and the southern face represents the control of evil.

Yoga spread across the Himalayas as the worship of Shiva, which was later embraced by Buddhism. While Hinduism emphasizes the transcendence of the self (ātmā), Buddhism focuses on the mind and interprets reality through that lens. These differences, which can be seen as semantic, have allowed Buddhism to incorporate Vedic gods without significant conflict.

Medieval Indonesian literature equates Buddha with Shiva and Janārdana (Vishnu). In present-day Bali, Indonesia, Buddha is regarded as the younger brother of Shiva, aligning with the notions of intelligence and intuition. Shiva and Vishnu are venerated in the popular Nīlakaṇṭha chant still sung by Buddhists in their temples.

Our consciousness provides us with a sense of time, and in Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism, Shiva is associated with Time (Mahākāla). In Japan, Daikokuten, one of the Seven Lucky Gods, represents a form of Shiva and holds a revered position as a household deity.

The influence of yoga has been so extensive that Hu Shih, a prominent figure in modern China and a key figure in the May Fourth Movement, declared in an essay titled “Indianization of China” that “India conquered and dominated China culturally for twenty centuries without ever having to send a single soldier across her border.”

Zoroastrianism holds a dualistic perspective of the world as a battle between good and evil. Over time, it integrated aspects of Hinduism into its system. Shiva Maheshvara was incorporated into the Zoroastrian pantheon of Central Asia. The god Zūrvan was portrayed as Brahmā, Ahura Mazda (Adbag) was depicted as Indra, and Veshparkar (Vayu in Sogdian) was represented as Shiva.

Svetovid, Svantovit, and the Coming Era

Among the Slavic people, there existed a practice of worshipping gods depicted with multiple heads in tall wooden statues placed in their temples. Alongside the three-headed god Triglav, the Slavs revered Svetovid or Svantovid, both names having Sanskrit origins: Svetovid meaning “knower of the light” and Svantovid meaning “knower of the heart.”

Svetovid, their primary deity, was portrayed as a four-headed god, and its main temple stood at Cape Arkona in what is now northwest Germany. This temple received offerings from all Baltic people until it was destroyed by Germanic invaders in the 11th century.

The four faces of Svetovid corresponded to Svarog (north), Perun (west), Lada (south), and Mokosh (east). Interestingly, the Sanskrit cognates of these names can be seen in Svarga, Parjanya, Ladah, and Moksha. Attempting to derive these names from indigenous European languages appears strained and unconvincing.

When exploring the connections more deeply, we find that they align with the four faces of Shiva described in the Mahabharata and also with the geography of Kashmir, from where the worship of Shiva likely spread to the Slavic lands.

In Kashmir, the gods were believed to dwell just north of the valley, in the Harmukh peak, which translates to the “face of Shiva” and corresponds to Svarga (heavens). The west of the valley, from where the rains originate, aligns with Perun, who scholars associate with Parjanya, representing Indra, the bringer of rains. The south of the valley corresponds to the pleasant land of India (Ladah meaning pleasant in Sanskrit), and the east represents the place where the sun rises, symbolizing the merging with the sun, which is understood as moksha (liberation).