A new study from IIT Bombay has uncovered how the bacteria responsible for tuberculosis survive antibiotic treatment by altering the composition and structure of their outer membrane. The findings shed light on one of the most persistent challenges in global public health: the ability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to endure even the most effective drug regimens.

A new study from IIT Bombay has uncovered how the bacteria responsible for tuberculosis survive antibiotic treatment by altering the composition and structure of their outer membrane. The findings shed light on one of the most persistent challenges in global public health: the ability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to endure even the most effective drug regimens.

Despite vaccination efforts and established treatment protocols, TB remains the world’s deadliest infectious disease. In 2024, an estimated 10.7 million people developed the illness and 1.23 million died from it, with India accounting for more than 2.71 million cases. The persistence of the bacteria during treatment has long puzzled scientists, especially in patients with latent infections that can reactivate years later.

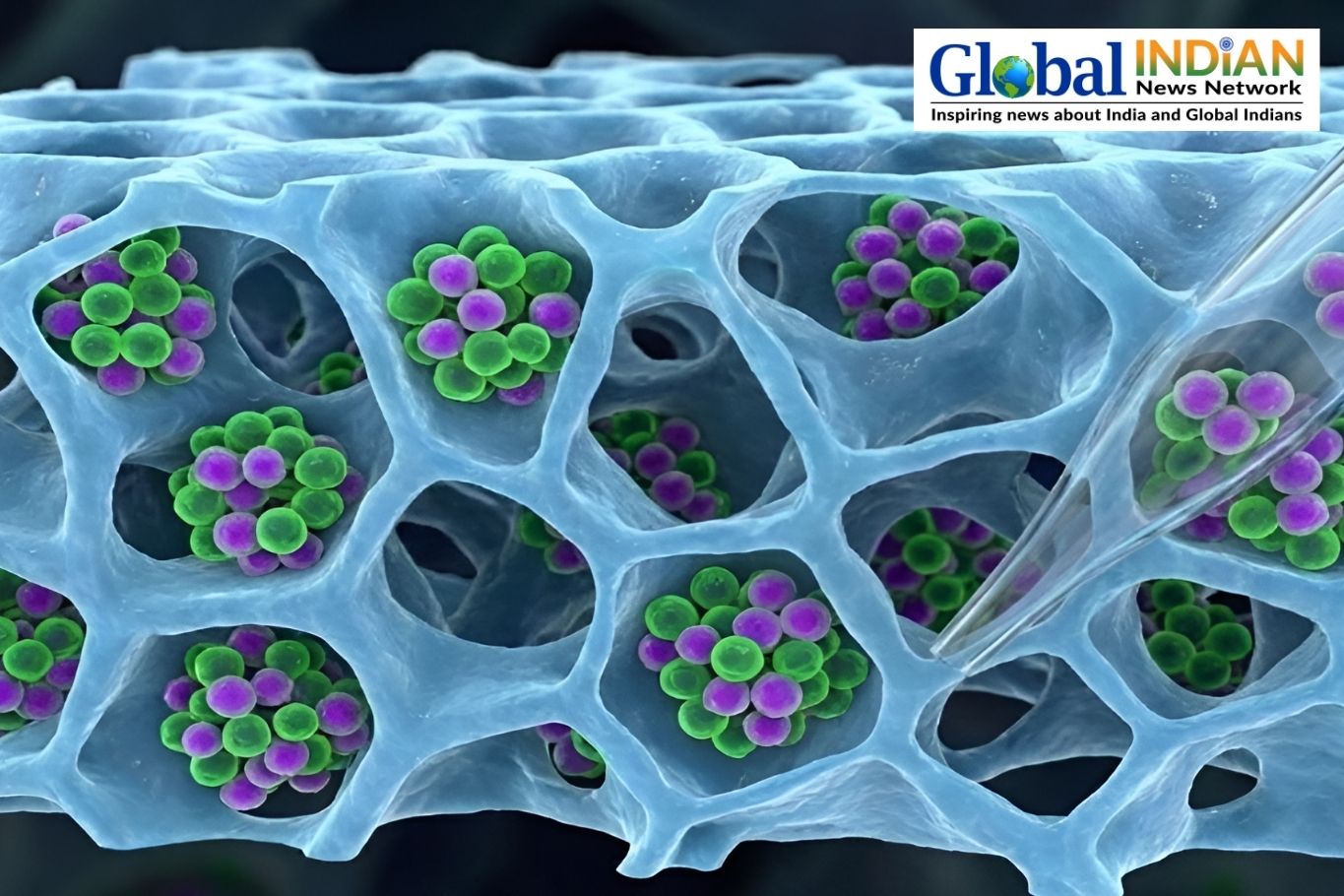

Published in Chemical Science, the IIT Bombay study shows that the bacteria’s survival strategy lies in their outer membranes, which are rich in lipids that act as protective barriers. Researchers compared the bacteria in two states: an active phase, where cells reproduce rapidly, and a dormant phase that mirrors latent disease. When exposed to four widely used TB drugs—rifabutin, moxifloxacin, amikacin and clarithromycin—dormant bacteria required two to ten times higher concentrations of antibiotics to halt their growth compared to active cells.

The study confirms that this drug tolerance is not driven by genetic mutations typically associated with antibiotic resistance. Instead, the shift occurs because dormant cells develop more rigid, tightly packed membrane structures, making it harder for antibiotics to penetrate. Researchers identified more than 270 distinct lipid molecules in these membranes, revealing clear biochemical differences between active and dormant states.

According to the study’s lead researcher, Professor Shobhna Kapoor of IIT Bombay’s Department of Chemistry, lipids have been underestimated in TB research. While protein-based mechanisms have been studied for decades, the role of lipid architecture in drug resistance has only recently come into focus. The team demonstrated that rifabutin could easily enter active cells but struggled to breach the fortified outer layer of dormant bacteria, highlighting the membrane as a crucial line of defence.

The findings open up possibilities for improving TB treatment by targeting these lipid barriers. Weakening the outer membrane could enhance the effectiveness of existing antibiotics without prompting permanent resistance. Kapoor noted that combining current drugs with membrane-loosening molecules could make persistent bacterial cells far more vulnerable, offering a promising path toward better outcomes for millions at risk.